The current COVID-19 pandemic is a global catastrophe on a scale that we’ve never experienced in business. It has forced choices upon us that a year ago we never thought possible – community versus economy, health versus wealth, freedom versus conformance, prioritising who to save and who to let die. In Australia, we are turning the corner. With smart choices, the worst could be behind us. Smart choices include learning lessons from the pandemic to strengthen our understanding of risk.

In the first week of February 2020, in the capacity as my organisation’s Chief Risk Officer, I developed a Coronavirus Response Plan. In doing so, I pored over information that was emanating from China. I checked in with global risk experts who were analysing probabilities of a broader pandemic. In my Collins Street office, I was playing out a range of ‘what if’ scenarios on the whiteboard. They all seemed bad:

- What if people are prohibited from coming into the Melbourne CBD? How does that even happen? Would the army patrol the streets?

- What if we become confined to our houses like in Wuhan City? How could that happen in a city of 5 million?

The possibilities were almost incomprehensible in Australia at that moment. Nothing like this had ever happened in our country before, so the prospect of it happening now seemed far fetched. My strongest memory of that time was a feeling of deep anxiety. The scenarios were ridiculous, even if the data suggested otherwise. I was anxious about my professional reputation if the scenario analysis was wrong. It would be a massive over-reaction if the virus didn’t travel. Discussing the topic with others didn’t help. Most were dismissive, unable to grasp the possibility of something that has not happened in our lifetimes. One-in-one-hundred-year events are like that.

And then the world changed.

Five weeks later we evacuated our CBD office and switched to home-based working, just as the plan outlined. Welcome to 21st century risk management.

What now?

Seven months later and many are planning for a ‘Covid-Normal’ business environment. COVID-19 isn’t going away any time soon. Our task is to be clear about our risk capacity whilst implementing a range of new compliance measures. Some of the emerging COVID-19 regulations will seem draconian and intrusive. But we have no choice but to work within the emerging regulatory system and not confuse compliance with risk.

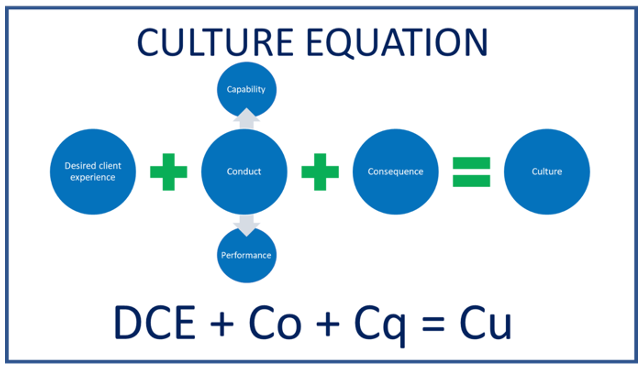

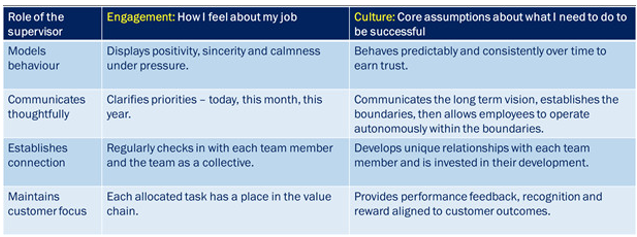

Our revised risk protocols will need to be understood by everybody in our business (clear appetites, tolerances, controls, roles and responsibilities) so that we can quickly identify and rapidly respond when things start to go wrong. Some customers and employees will invariably have personal risk tolerances that vary from our organisational tolerances. Outlier behaviour cannot be the reason your business gets shut down. Behaviour such as refusing to wear a mask, refusing to physically distance or even refusing to come to work is foreseeable and there are no excuses for failing to have plans in place that protect the system.

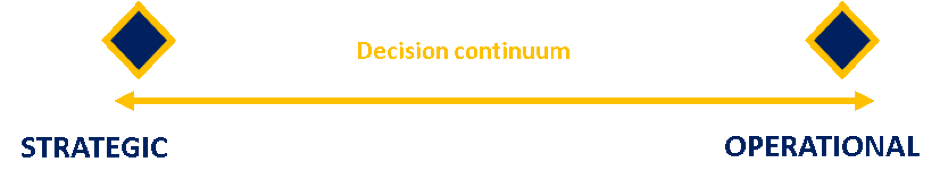

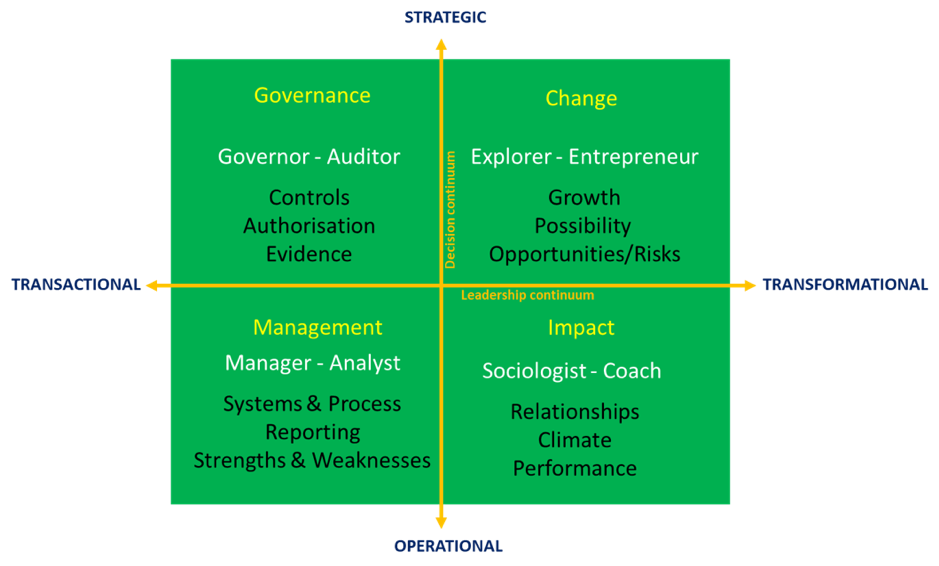

Tactical verses strategic risk management

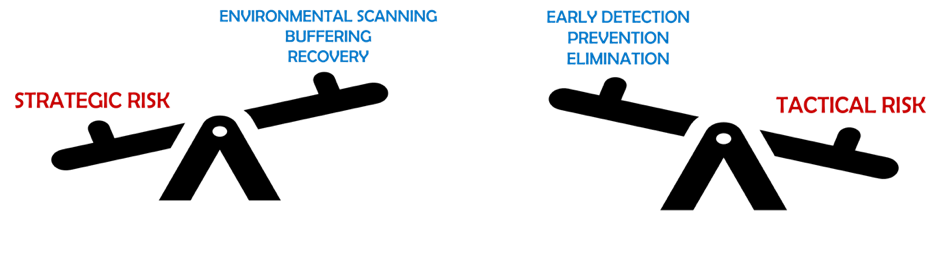

Tactical risks mostly involve those things where the solution lies inside your business, and therefore can be controlled. If you can control the risk, then you must. Focus on early detection, prevention and elimination.

Covid Safe Plans are an example of tactical risk management. Tactical risk management will necessarily dominate our thinking in coming months, as this is what will be required to get us operating effectively again and restore community confidence. This includes things like pedestrian circulation plans for your retail store, indoor and outdoor patron dining plans for your cafe and smart ticketing options for your sporting events that enable rapid tracing should an outbreak occur.

Tactical risk management is critical but will not be enough. That is why we must devote much more time to strategic risk management.

Strategic risks, in this context, mostly concern events which are external to your business and cannot be controlled. When they occur, they materially impact your business. The big strategic risks need to be considered and addressed differently to the tactical risks. At the heart of this difference is accepting that you do not hold the levers of control. No matter how well you prepare, big external events will still occur that may severely disrupt your business. So instead, place your focus on environmental scanning, buffering and recovery.

To assist in my environmental scanning, I allocate strategic risks into six mega risk categories:

- Habitat risks – destruction of the natural environment, often but not exclusively climate related, leading to irrevocable changes to ecosystems.

- Biological risks – such as COVID-19, which is dominating our lives right now.

- Water security risks – security and supply of water is fundamental to human survival. Breaches of water security bring life to a halt within days.

- Cyber risks – see how far you get into your day if you cannot log into the system tomorrow, if the traffic lights don’t work or if your smart phone is unresponsive.

- Energy risks – The engine room of industry and the basis of movement around the globe and across town. Do you even own candles and matches?

- Food security risk – Protection of food sources and supply is fundamental.

You might develop different risk categories to these. The important challenge is to think on a global scale and consider the potential events that might occur, which would impact your business. Risks may be indirect, such as impacts to supply chains, or direct, such as cyber-attacks.

Strategic risk management requires advanced ‘what-if’ capability. COVID-19 has demonstrated that business leaders must develop skills in looking over the horizon to those things that might occur and developing plans to survive and overcome these mega risk events. Strategic risk management requires understanding and application of systems logic and its intersection with the complexities of human behaviour, often at scale.

Strategic risk management accepts that bad stuff is going to happen. Your task is to build a buffer into your operating model that protects your business from the immediate impact of a risk event. That gives you the most precious commodity – time.

Most importantly, strategic risk management requires us to practice failing and recovering. Do it regularly and make it the centrepiece of your risk culture. Regular scenario testing of disaster events and demonstrating your capacity for recovery builds resilience and confidence in your workforce. The first time you discuss how you might respond to denial of service and ransom demand from a Russian hacker better not be on the day when it happens.

The next mega event won’t just be a pandemic

We now know what a pandemic is. We also know that global and local connectedness has resulted in COVID-19 spreading faster than we could have ever imagined. Global connectedness, instant communication, ease of travel and access to information has created co-dependencies across economies and communities that will only increase. COVID-19 will re-set some of the rules of engagement and it will take some time to find a new normal, but we will return to most of the patterns that we once had.

But the mega risks are only going to increase. Old thinking about one-in-one-hundred-year events will be re-baselined. Pandemic risks will be rated as one-in-five or one-in-ten-year events from now on. But the real threat is the increasing probability of overlapping mega risk events.

This year in Australia, we had an eight-week gap between catastrophic bushfires along the east coast and the onset of COVID-19. Consider for a moment if those events had overlapped? Now add to the catastrophe the possibility that our telecommunications networks could be attacked and be off-line at the same time.

Risks that are complex now, will become chaotic when they merge. We need to be prepared.

So where do we start?

Begin by splitting your thinking and effort across strategic risk and tactical risk.

Revisit your risk registers. What is the mix of internal events and external events? There ought to be a balance of strategic and tactical risks, that makes sense for the business and the industry that you are in.

Don’t allow your risk registers to be clogged with ‘People and Culture’ risks. When that occurs, it signals a culture of management avoidance. If you have people and culture issues, deal with them as a leadership priority. Addressing people issues will have a materially beneficial impact on long term risk culture.

Finally, learn to accept the discomfort that risk events never occur in the isolated way they are described in our risk registers. Your risks are linked. In the new era of mega risks, overlapping events will occur simultaneously. Your risk eco-system is connected in a subtle but complex way, often with the intersections occurring at the human level. When things start to go wrong, it is likely that problems will appear on several fronts. Whilst they may seem disconnected, they are likely to be highly connected, requiring systemic responses.

If you find yourself playing ‘whack-a-mole’ with a myriad of issues in your business, then ask whether you are dealing with strategic or tactical risks? Am I trying to control scenarios that cannot be controlled? Is your energy therefore better directed elsewhere? The answers may surprise you.